The world’s tallest roller coaster has been one of the hardest record’s to keep track of. Parks, seeking publicity and attention such a claim gives, have been quite creative in ways to claim it. In this Serie of articles, we will look at the verified height of roller coasters throughout the year and show that rides in Japan were ignored for the longest time due to distance in the pre-internet days and Japanese domestic suppliers not open to overseas business. Parks could exaggerate the speed, height, and length of their attractions with no easy ways to counter-verify.

Online data can be inaccurate, so we reached out to parks and manufacturers themselves for the most accurate data possible. Given the tools available to us now, we will describe the detailed list of record holders, starting when roller coasters were purpose-built as amusement machines versus repurposed railroad tracks in the 1800s and wooden ice-covered slides.

After riding the famed Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway in Pennsylvania, a nine-mile long mining railway turned into the world’s most incredible ride; La Marcus Thompson had the idea to bring a similar experience to parks around the world. Due to the unusual setting and history behind the Mauch Chunk Railway, it was impossible to replicate it.

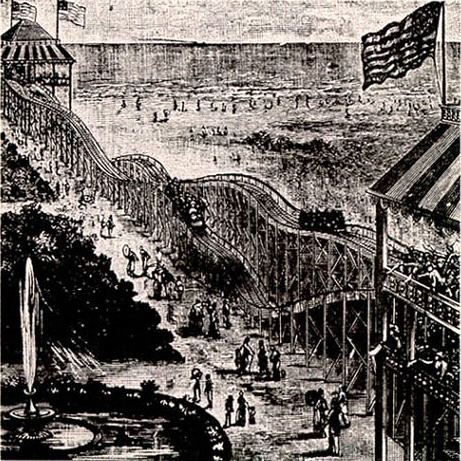

The Gravity Pleasure Switch Back Railway opened in 1884 at Coney Island, on a concession held by LaMarcus Thompson. The ride was 50 feet tall and was composed of two platforms separated by two 600 feet long sections of gentle dips. The single-car reached six mph as it rolled down to the ground. Once at the bottom, guests exited the car, and staff pushed it up to the other tower, where more guests boarded it. The prototype was short-lived but provided proof that the concept worked. The roller coaster evolved into an oval, which leads to the famed Scenic Railway style of roller coasters.

John A. Miller was part of LaMarcus Thompson’s company when he was 19 and eventually became its chief engineer. By 1910, after seeing all the safety challenges that roller coasters had at that time, he came up with two inventions that allowed roller coasters to reach new heights, speed and safety. The first came in 1910 with the anti-rollback device used to prevent a car or train that stops on a lift hill from sliding back down. It uses strips of metal teeth that have a rectangular triangle shape mounted somewhere on the lift hill. A device is installed on the roller coaster car that can slide on the anti-rollback strip’s angled part but will get stuck on the straight section, preventing the vehicle from moving backward.

The next invention came in 1919 and was as critical: Miller Under Friction Wheel or upstop wheels. Previous roller coasters relied on careful designs, grooved paths, or metal bars to prevent the wheels from lifting away from the track. The upstop wheel is attached to the primary road wheel carrier, combined with a track that has space under the main running board or surface, prevents the car from moving away from the path, allowing steeper drops and more aggressive hills.

On the subject of keeping the cars from derailing or sliding laterally off the track on rides today, two theories exist railroad-style flanged wheels or guide wheels. Flanged wheels are shaped so that a part protrudes down when they are rolling; combined with the other wheel, they prevent the car from sliding excessively left or right. The second idea is to have one or two guide wheels mounted to the bogie that holds the road and upstop wheel together, locking the car to the track. This is how most modern roller coasters are configured, and we can thank John Miller for that fantastic innovation.

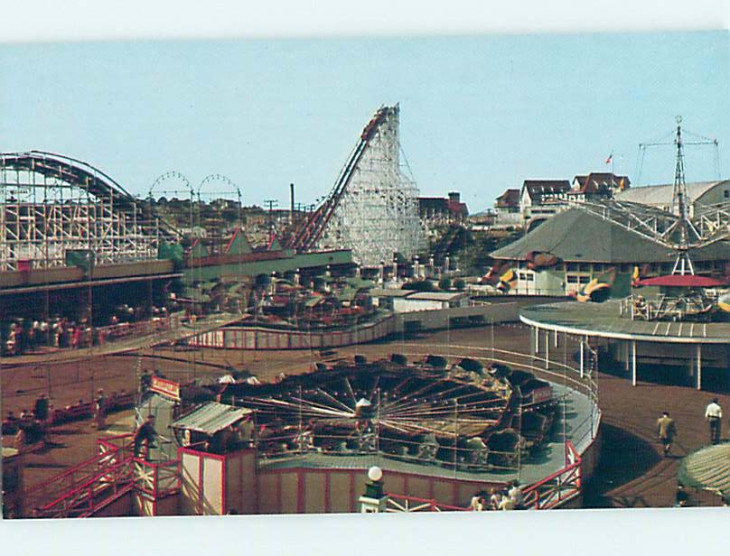

Starting from 1911 until 1920, John A. Miller was a consultant to the Philadelphia Toboggan Company (PTC), which had started building and operating roller coasters as concessions at amusement parks and boardwalks. The world’s tallest roller coaster in 1917 came from this collaboration, where John A. Miller designed the Giant Coaster at Paragon Park, and PTC built it. Located south of Boston, MA, near the Ocean, the ride stood 98 feet tall and was a side-friction design with a double out and back track layout. Paragon Park suffered some dramatic fires that lead to intensive modifications on the Giant Coaster. The first one happened in 1932 and lead to a dramatic redesign of the roller coaster.

Herbert P. Schmeck had helped construct the original coaster, and at that time, he was called on to rebuild the unfortunate ride on a sensible budget. The extensive initial double and back configuration and the massive side-friction configuration were too expensive to rebuild. He remade it as a simpler out and back with a dramatic double helix finale that used modern (for the time) PTC trains equipped with upstop wheels.

The ride suffered another fire in 1963 that destroyed the station, trains, double helix, and the bottom part of the lift hill. John C. Allen, a student of John A. Miller, was tasked with rebuilding the ride during his time as PTC president. The park asked him to restore it as an exact copy of Herbert P. Schmeck fantastic layout, but it was again too cost-prohibitive. The compromise was a new approach to the plan before the twin airtime hills that were destroyed. Brakes were mounted on that curve along with a new station. The last part of the puzzle was found at Forest Park Highlands Amusement Park in St. Louis, MO. The Comet roller coaster was also severely damaged by fire and would not return to service. The trains were spared, and Paragon Park purchased those trains, which dated back to 1941, for the Giant Coaster. As an interim measure, until the Comet trains were ready, National Amusement Devices trains from the Crescent Lake (Providence, RI) Zephyr, which closed in 1961, were purchased.

Paragon Park closed in 1984, and the roller coaster was purchased by Wild World, a zoo that was returning rides to its parks at that time. They hired the Dinn Corporation to take down the roller coaster and rebuild it at its new home in Upper Marlboro, MD. They were able to pay homage to the original finale with a new helix and airtime hills. A new transfer track outside of the station to store a train was also integrated, thanks to the extra land available at its new location. The ride was renamed the Wild One and opened to public acclaim in 1986. The ride still operates under the same name at Six Flags America, the current name for Wild World.